Weaponizing the Internet: The Next Decade of Cybersecurity

Weaponizing the Internet:

The Next Decade of Cybersecurity

Written for JESPIONNE

Anastasia Iva Xavier

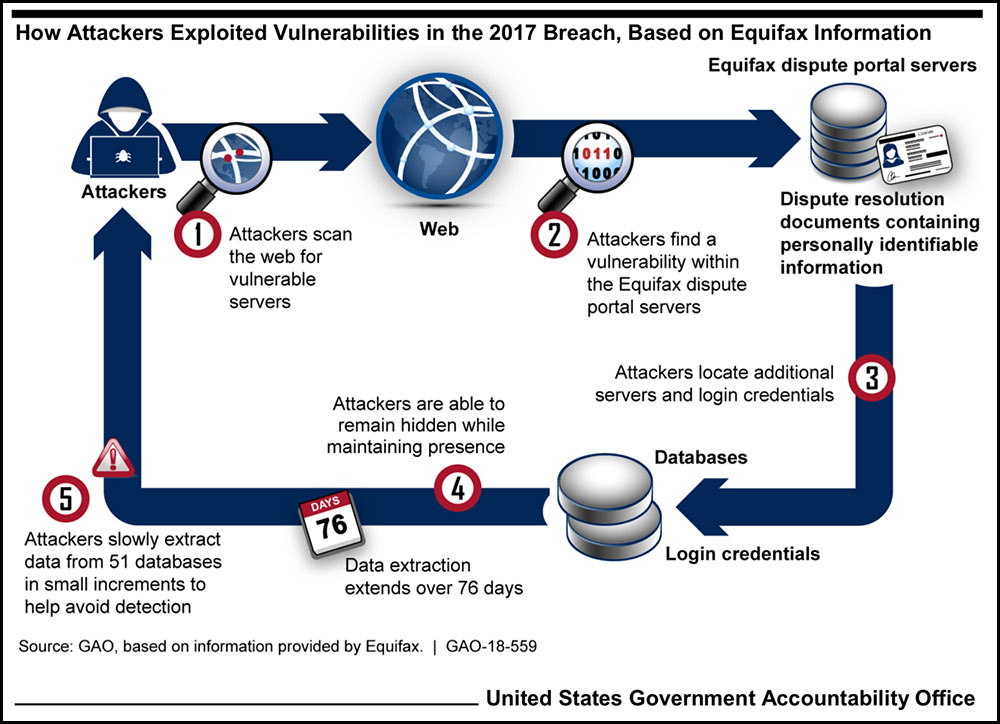

Perhaps one of the greatest cyber-attacks in history, vulnerable web application Apache Struts was used to target the personal data of 147 million Americans in the 2017 Equifax Data Breach. A piece of software, tricking the application into running malicious code, created unknown millions of dollars’ worth of damage.

The Equifax case is one of many recent cyber-attacks by both government and non-government organizations (NGOs), all seeking to infiltrate both private and government networks. The target of these attacks is personal data, infrastructure, power grids, and even surveillance equipment, with a goal of disrupting or stealing information.

"T he history of cyberwarfare will always begin with Estonia."

- Estonian President Toomas Hendrik Ilves (2006 – 2016)

January 2021

DOS/DDOS Attacks

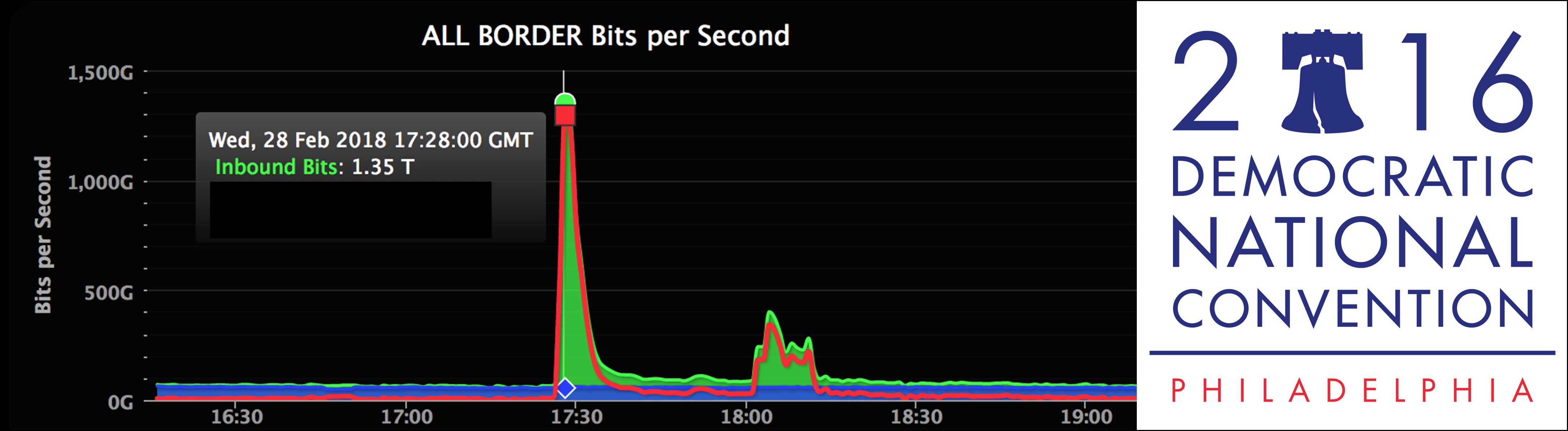

Attacks can occur in various ways; Denial of Service (DoS) and Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks can overwhelm any network or system, causing a complete overload and shutdown. The largest DDoS attack ever recorded targeted the popular software developer GitHub in 2019. Almost 1.35 terabytes of traffic per second attacked GitHub at the same time, an unprecedented amount of data requests.

This was achieved by utilizing Memcached servers; Memcached servers are owned by businesses and institutions and sit online without any authentication defense. They can be sent queries and accessed by any IP address. In 2018 attackers used the IP address of GitHub to access these servers, routing all the much larger responses to GitHub. This type of DDoS attack is known as an amplification attack and has become increasingly common due to ease of access. While the damage was mitigated with third-party help, the attack was widely seen as a successful attack, as the traffic was sustained for over 20 minutes.

More commonly, smaller attacks between 50 and 500 gigabits per second are being seen around the world, increasing concerns of how private individuals, corporations, and governments can handle such assaults, especially if they occur at the same level as the GitHub attack. Taking down or increasing encryption on Memcached servers is one way to handle DDoS attempts, but no firm solution has presented itself, as more Memcached servers are being sought everyday by hackers.

Phishing Scams:

Another major cybersecurity threat is phishing, a hostile link usually sent through email, result in sensitive data being stolen. Coupled with malware, a malicious software designed to hold accounts and information hostage on the computers it infects, accounts for 90% of all system data breaches. Phishing scams alone are reported to have targeted 76% of businesses in the last year.

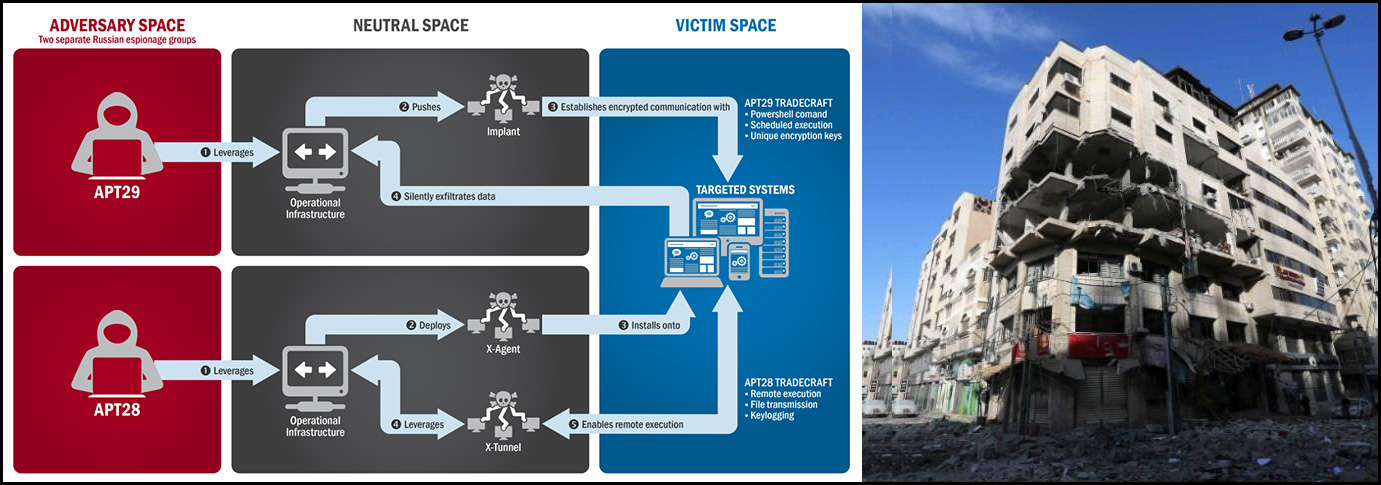

One of the highest profile phishing scams of the last few years targeted the Democratic National Committee (DNC) in 2016. The hacking group known as Fancy Bear utilized fishing links to gain access to private emails and accounts of members of the DNC, exposing some of the DNC’s inner workings and the group Cozy Bear, who had gained access several months before hand. Cozy Bear maintained observation on the DNC and was only detected after the Fancy Bear attack.

Both Cozy Bear and Fancy Bear originate in Russia and are connected to the Russian Security Service. Phishing attacks use a combination of social engineering to trick people into opening links and are hard to defend against. Because the level of effort going into a phishing attack is so low, it is an attractive option for a single individual, and even more powerful for groups.

Future Responses to Cyber Threats:

Few nations acknowledged the use of cyber-attacks to further policy abroad, and most

attacks originate from NGOs. Likely directed by state powers, NGOs who perpetrate attacks seek to protect their own anonymity, creating identification problems. As an extension of the identity crisis, countries who cannot identify their attackers cannot respond. When they do, however, there are usually reprisals. For example, in 2019, cyber-attacks originating from a Hamas building were targeted in an Israeli bombing campaign. The building was destroyed, and Israel claimed a successful operation. This raises the question of what type of response do cyber attacks warrant.

In 2016, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) stated any cyber-attack on one country will trigger a collective military response from the entire alliance. Cyber attacks are also now becoming a common response to military action. In June 2019, Iran downed a US surveillance drone over the Straits of Hormuz. In response, the US targeted key infrastructure in Iran, attacking computer targeting systems for missile and rocket launchers throughout the country.

With cyber attacks by state entities becoming more prevalent, countries are seeking to combine their newfound capabilities with conventional action. One of the most practiced in this regard is Russia. In the 2008 invasion of Georgia, the Russian Federation used a combination of cyber and conventional attacks to knock out Georgia’s information sharing systems, and during the Crimean Conflict, unexplained blackouts occurred through much of Crimea and the Donbass regions. Attributed to Russian NGOs, the blackouts spread discontent throughout Ukraine allowing Russian backed separatists to gain traction in the East.

Cyber-attacks are relatively cheap, with little to no risk for the initiating party, and can have wide ranging effects. With few acknowledged attacks, hundreds more occur each day, and the danger is ever increasing. Not capable of fully replacing a conventional military, cyber attacks and intelligence gathering instead augment them, and increase the effects of a coordinated attack. As seen with the Russian invasion of Georgia and the Crimean Conflict, the combination of both cyber and conventional forces can secure victory. It is likely that exploration of cyber capabilities will continue, but who will be on the receiving end of such attacks?

Moving Online:

In 2020, administrative centers for countries are moving online. To reach each citizen, countries are expanding internet access at an unprecedented level. Some, like Estonia, have opted to go completely online, doing away with physical documents, in-person voting, and even banking activities. While a seemingly ingenious leap into the future, electronic has placed Estonia in danger.

In 2007, Estonia was targeted in a country-wide attack which crippled the country, resulting in riots and general unrest as people could not access vital resources. Most IP addresses targeting Estonia in 2007 pointed to Russia, but the identities of the attackers are unknown. Requests for help from the Russian government in identifying the perpetrators were ignored, and Estonia was left to fend for itself. In the years following the several weeks long attack, Estonia has ramped up their cyber security. Estonia now boasts one of the best cyber security groups in Europe, and fights on the frontlines of cyber warfare, everyday against network attacks.

Responses to growing cyber threats cannot be made in fear. Estonia’s success in curtailing cyber attacks since 2007 grows after each instance, and the country is asserting its cyber control. In response to growing threats, it is likely other countries will begin to band together, creating intelligence and data sharing organizations to bolster defenses, much like the Five Eyes network seen in the intelligence community.

Moving Online:

Positive action, rather than reaction, is required to mitigate destructive cyber activities, and only through action can data be protected. A new age of information sharing is upon us, and threats continue to emerge and grow as development occurs. Secure online presence is essential in the modern era and staying ever vigilant against cyber threats is a must.

Photos

Democratic National Committee/ Garanich, G./ GitHub & Akamai/ NATO/ RS Kingdom/ Stringer/ The New York Times/ United States Computer Emergency Readiness Team/ United States Government Accountability Office/ Zero Day

TAGS

Cybersecurity/ Russia/ Estonia/ Democratic National Committee/ DNC/ Equifax/ GitHub/ Fancy Bear/ Cozy Bear/ Israel/ Hamas/ Georgia/ Ukraine/ Crimea/ Phishing/ DOS/ DDOS

December 2020