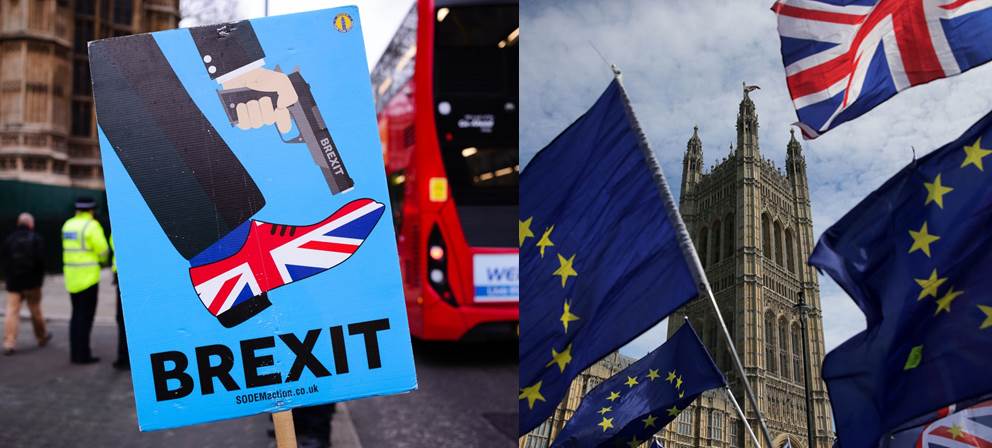

BORIS JOHNSON’S PLAN TO SOLVE BREXIT

CoCoP: COMMUNICATING COHESION POLICY

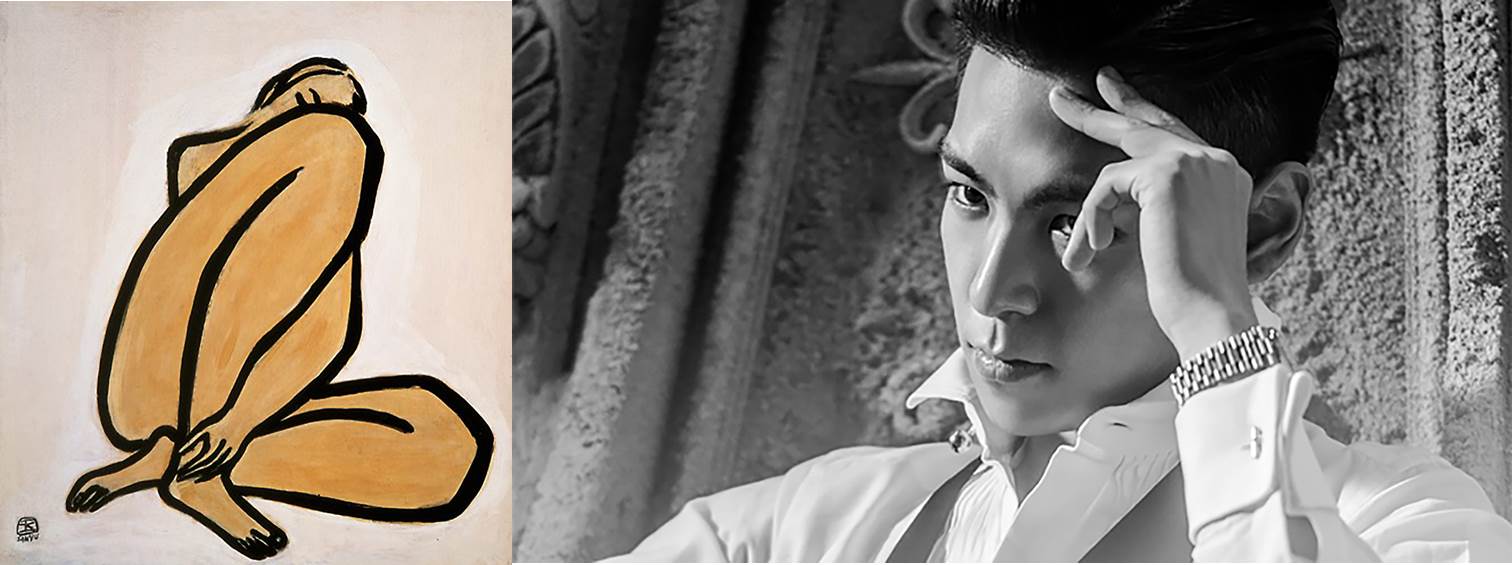

Written for JESPIONNE

Emelie Rose Beauvoir

Britain’s withdrawal from the European Union was a global surprise. The referendum spurred a bevy of theories to explain its cause; some cited malice and underrepresentation of minorities in the UK’s ‘first past the post’ voting system while other popular notions held a misunderstanding of the referendum’s implications.

The factors that initiated the withdrawal herald significance and a foreboding of the region’s stability with the growing trend of populism. Nonetheless, the UK and its EU contemporaries must now delegate a mutually beneficial deal that pays full adherence to the UK’s isolationist will, whilst the EU foresees to negate the prospect of other opt-outs in its organization.

Boris johnson, the newly elected prime minister of the uk, identified the barrier to brexit as the ’pessimists’ who are reluctant to believe in a glorious post-brexit future.

July 2020

The UK faces an economic downgrade of proportions unexperienced since the Second World War. The EU agreement is bound by a complex system regarding employment, citizenship, and trade deals across member countries and renegotiating these points is contingent upon Britain’s competence to settle dissenting opinions within its parliament—the body’s constant flux of pending implications for the future currently lack formidable leadership and direction. However, the outcomes of both full

compliance and settlement on a compromise are iced over and yield hardened results, given the stipulated time constraint and lack of options available to ensure a favorable exit. The business networks within the UK will eventually transform existing EU laws to a standard in accordance with independent UK codes. The ability to adapt to these jolts is a product of successful cooperation and implementation by parliament, but frankly under a graver influence of Eurosceptic attitudes and the growing populism.

Boris Johnson, the newly elected Prime Minister of the UK, identified the barrier to Brexit as the ‘pessimists’ who are reluctant to believe in a glorious post-Brexit future. Reminiscent of Donald Trump, his bid to ‘make Britain great again’ is a powerful move that sets the nation’s scope on an isolationist and narrow objective, that is, optimizing Britain’s

preeminence at the expense of all other priorities. Johnson motioned that if parliament is unable to come out with an agreement by October 21st of 2019, then the UK will leave the EU without a deal, a ‘hard Brexit’. A ‘no-deal’ agreement under Theresa May once appeared off the table as an overwhelming majority of MPs demonstrated in a vote that it would be

catastrophic and ill-advised. Previous deals have gone unnegotiated and without substantial direction. In 2018, the UK and the EU agreed on a general exit deal, but many specifics of the deal were met with staunch disposition. A vote supported by all 27 EU members approved a request to have

the existing deadline extended, protracting the mutually agreed closure for both agents. To the dismay of many Brits, Brexit might seem an illogical and prescient exemplar of an incompetent administration, but for international politics, perhaps such a move will yield results drastically in their favor.

Reference Article

Reference Article

By HELEN LEWIS for THE ATLANTIC

What has stopped Britain from leaving the European Union, three years after it voted to do so? Is it the difficult negotiations over the Irish border? The cold facts of parliamentary arithmetic? Or is it the nebulous nature of Brexit itself, wherein 52 percent of Britons delivered a vague mandate to Leave and left it to politicians to fill in the details? No, according to Boris Johnson, Britain’s new prime minister; it is none of those things. Outside 10 Downing Street today, he identified the real barrier to Brexit: a lack of optimism. “It has become clear that there are pessimists at home and abroad,” said Johnson, bouncing on his heels with the enthusiasm of a Labrador. He attacked the “doubters, the doomsters, the gloomsters” who do not believe in Britain’s glorious post-Brexit future or its ability to reach those sunlit uplands. “The people who bet against Britain are going to lose their shirts,” he added. These stirring yet vague demands for positivity were a regular feature of his campaign for the Conservative leadership. His final column for The Daily Telegraph—one he was paid £250,000 ($312,000) a year to write—argued that more “can-do spirit” was needed to resolve a puzzle that has tormented Parliament for months. After all, he wrote, “if they could use hand-knitted computer code to make a frictionless re-entry to Earth’s atmosphere in 1969, we can solve the problem of frictionless trade at the Northern Irish border.” (It was left to scientists to point out that Apollo 11’s reentry was not “frictionless”—that is why it had heat shields. Johnson might also have mentioned that the moon mission was the culmination of years of intensive planning and preparation.)

To the 90,000-odd Conservative Party faithful who elected him (a “selectorate” that forms less than 1 percent of the British population), none of this matters. Johnson has told them that everything is going to be okay, and they want to believe him. More than anything else, they are bored with discussions of trade deals, nontariff barriers, and regulatory orbits. He promises entertainment and novelty instead. In this reading, the greatest flaw of Theresa May, Johnson’s predecessor on Downing Street, was not just failing to pass a Brexit deal, but doing so in such a dull, repetitive fashion. The possibility of a No-Deal Brexit is exciting, in the way that stories about the Second World War—and Johnson’s hero, Winston Churchill—are exciting. It is a viewpoint that can flourish only now that so few people remember the reality of that time: rationing, air raids, death. There’s a reason that “May you live in interesting times” is considered a curse. Johnson’s addiction to optimism is reminiscent of Donald Trump’s promise of endless victories. “We’re going to win so much, you’re going to be so sick and tired of winning,” the U.S. president said in April 2016. The new British prime minister offers a similarly enticing prospect: a world without compromises or awkward concessions, a world where Britain is once more recognized as a great power (back to the Second World War again). It is patriotism on protein powder READ MORE >>

So perhaps his No Deal preparations, directing the civil service to ramp up planning for such a scenario, are not a bluff. Today, he repeated his campaign promise to leave by October 31, with or without an exit deal, “no ifs, no buts.” (It is a phrase with an unhappy history: Former Prime Minister David Cameron used it in 2011 when making his pledge to lower net migration into Britain to fewer than 100,000. He failed repeatedly.) The rest of the speech proved that he has two modes: buffoonery and boredom. It was light on jokes. There was, mercifully, no Latin. It merely dabbled with the self-satisfied wordplay that filled his newspaper columns, such as calling the four nations of the United Kingdom the “awesome foursome.” Parts of it sounded like May’s own Downing Street speech after she became prime minister in 2016: high aspirations about social justice, all eaten by the relentless grind of European negotiations.

The tragedy of May’s speech three years ago was that it barely mentioned Brexit, the issue that consumed her premiership and led to her downfall. At her last Prime Minister’s Questions today, she tried again to create a different legacy. She saw her success in “the opportunity of every child who is now in a better school, in the comfort of every person who now has a job for the first time in their life, in the hope of every disadvantaged young person now able to go to university, and it is in the joy of every couple who can now move into their own home.” This is how she would measure her record, she said. She will be the only one to do so. To history, May will be the prime minister defeated by Brexit. Will Boris Johnson be remembered the same way? His insistence that he is prepared to leave the EU without a deal—risking interruptions to food and medicine supplies—has already prompted several senior members of the cabinet to quit.

They include International Development Secretary Rory Stewart, who coined the most durable sound bite of the Conservative Party leadership contest that Johnson eventually won. When Stewart tried to stuff three garbage bags into his bin at home, he said, his wife told him off. Instead of accepting that she was right, he was tempted to tell her, “Believe in the bin!” Brexiteers had a similar approach, trying to magic away problems by declaring, “Believe in Britain!” The past few weeks have been very “believe in the bin.” The cabinet has been reshaped with the appointment of hard-line Brexiteers such as Dominic Raab, who resigned as Brexit secretary because he saw May’s deal as too weak—and has called for Parliament to be suspended

if it refuses to accept a No-Deal Brexit. “In 99 days’ time, we’ll have cracked it,” Johnson announced this afternoon. “The British people have had enough of waiting.” Except, of course, they have a little more waiting to do. Parliament breaks up for the summer tomorrow and does not return until September. If Johnson has a new deal, it will be more than a month before we find out whether it can pass the House of Commons. “To all those who continue to prophesy disaster, I say yes—there will be difficulties, though I believe that with energy and application they will be far less serious than some have claimed,” said Johnson. We live in interesting times.

Photos by

Assoicate Press / Politico / Original Source Article

TAGS

Angela Merkel / Syrian Refugees /German Chancellor / Josef Janning / European Council on Foreign Relations / Berlin / European Security / Brexit / Greece Financial Crisis / Person of the Year / Politico / Mathew Karnitsching

July 1st, 2020

INTERVIEWS